Spinning wheel illusion

In the era of Covid-19 (because it feels likes an era!), where reality seems very unreal, allow us to distract you with some illusions 😉

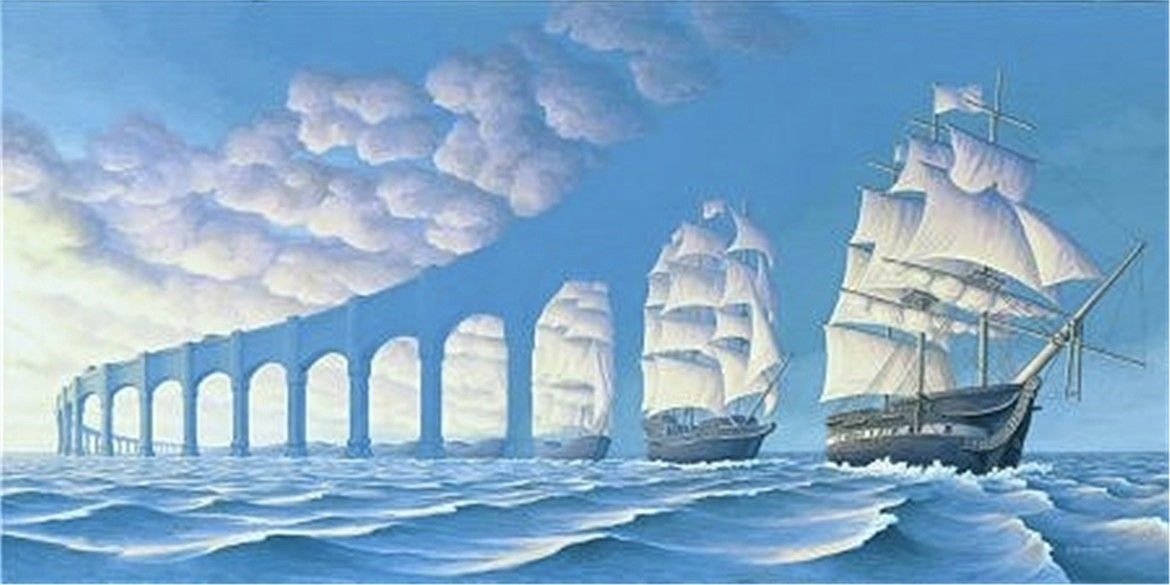

Everyone loves a good magic trick, which is usually spoiled once you know the behind the scenes of the ‘trick’. Well, let me introduce you to real life tricks our brain plays on us all the time!

Is seeing believing?

Perhaps, not always….watch this clever ad by the SKODA car company that shows a well known phenomenon known as change blindness: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qpPYdMs97eE. Our brains have finite resources and there is simply too much going on in our environments for our brain to pick up all of it. The result, illusions like change blindness, show up these gaps in our perception vs. actual reality. This illusion shows how limited our attentional resources are. Everything isn’t always as it seems!

Now, let’s take a trip down memory lane to 1985, the year of the moving statues.

Here in Ireland, religious statues began to move left right and centre sparking international attention. People flocked in their thousands to watch these miraculous movements. In one town, Ballinspittle in Co. Cork, hundreds of people said they saw the statue of Holy Mary nod or sway. Are you sceptical? Well the clergy certainly were, saying such mass miracles were unlikely. Well, the statues have since stopped moving and nobody can be quite sure if the statues were shaking or not, but science puts it down to a trick of the light; an optical illusion. In Ballinspittle, people stood for hours on end on a grassy incline opposite the grotto, watching in the dusk to see Mary move. Scientists explained a possible reason for the mass sightings. Our bodies when standing still, naturally sway without our realising it and psychologists claimed people (or their brains) picked up on this movement but ‘saw’ the statue move rather than interpreting that they themselves were moving). A similar effect is called the motion aftereffect (or the waterfall illusion), where after just seeing something moving, we perceive a stationary object as moving, try it out for yourself: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=95&v=GkRHN0rnfME&feature=emb_title. It’s thought these illusions happen because of how our visual cortex and vestibular (or balance) system operates [1].

Perceptual illusions can also explain paranormal activity. The Ouija board for example [2]. How can science explain that? A wooden board able to tell me the name of my dead dog? Science says, no problem, what you’re talking about is the Ideomotor effect. The ideomotor effect is simply that you aren’t consciously aware of everything your brain tells your body. When you sit in a circle with your supernatural sidekicks and place your hand on the upturned glass and gasp when the glass moves and spells out MAX, little do you know your brain is pulling the wool over your eyes. Without any wool! Your brain is unconsciously guiding your arm towards the letters that spell out your dear dog’s name. Et voila, some dark magic before your very eyes!

Illusions as windows into brain functioning

Aside from the fun and games, perceptual illusions are fascinating, not just for magic tricks and understanding some unexplainable stuff in our lives but also for research. Our lab deals with a less glamorous but important illusion, the Sound-induced flash Illusion. It does exactly what it says on the tin, you can induce an ‘illusory’ flash by playing a sound. Your ears pick up on a beep and your brain sees a flash that doesn’t exist. Pretty neat eh? Well, this illusion allows us to measure how well the brain integrates information from different senses. Based on how susceptible you are to (i.e. how often you ‘fall’ for) this illusion, we can estimate how efficient your brain is at integrating information across the senses. This illusion has great potential in the field of falls, with studies showing fall-prone older adults are more susceptible to this illusion than others, indicating a possible deficit in their sensory integration abilities. Could this be contributing to their falls? We’re looking into it! Watch this space!

References:

1 Anstis, S., Verstraten, F. A., & Mather, G. (1998). The motion aftereffect. Trends in cognitive sciences, 2(3), 111-117.

2 1 Gauchou, H. L., Rensink, R. A., & Fels, S. (2012). Expression of nonconscious knowledge via ideomotor actions. Consciousness and cognition, 21(2), 976-982.